This is the first in a series of articles aimed at introducing the French poster-maker Charles Loupot to an English speaking audience. Loupot was one of the most prolific and celebrated graphic artists of his age, but his legacy has disappeared. Virtually unknown even to many art historians, it is time that Loupot is recognised for his contribution to the story of art. What follows is a brief foray into the distinctly French world of L’Affichage – the art of the poster.

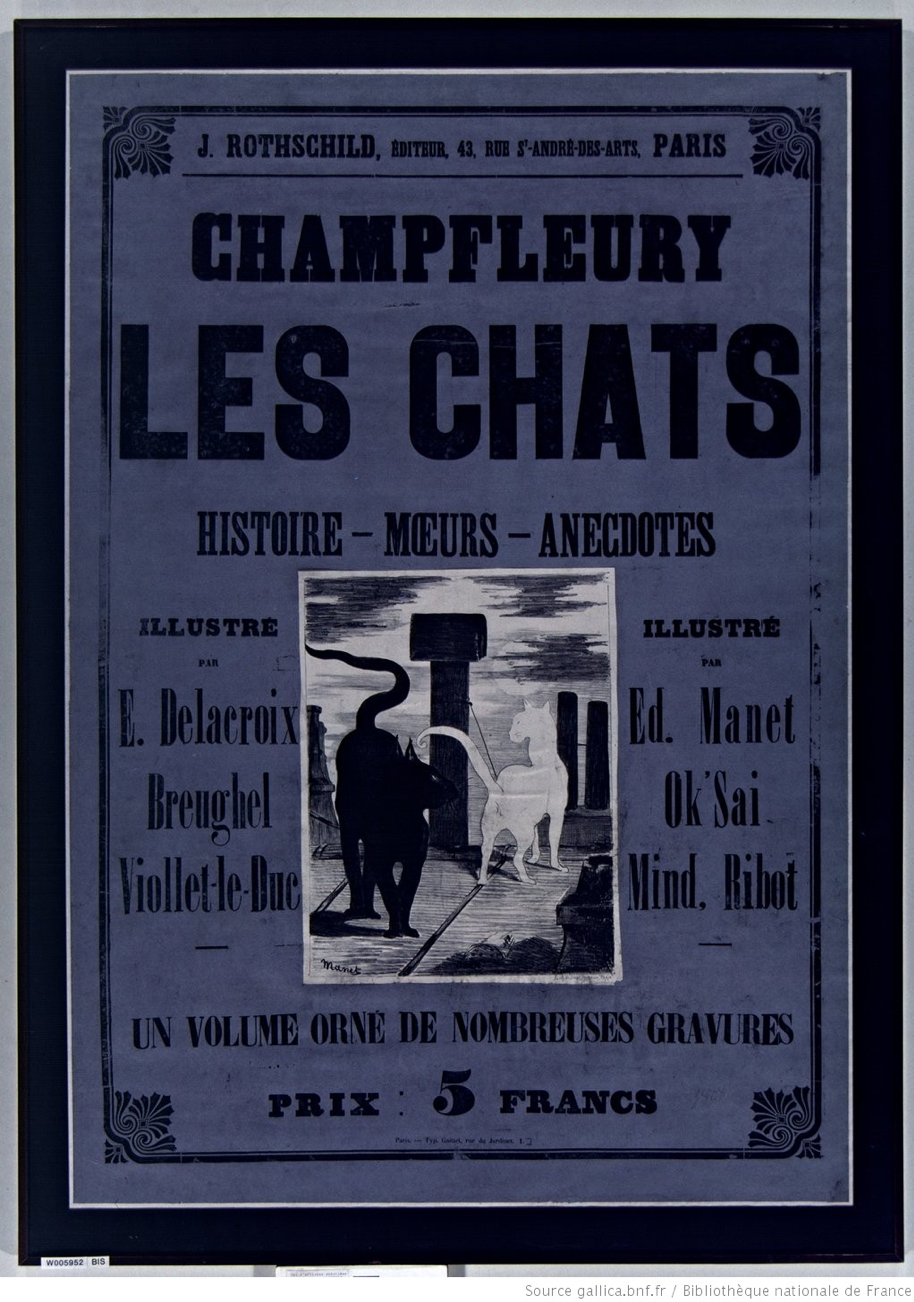

Perhaps more acutely than any other time,the twentieth century demanded a radical re-evaluation of exactly what the image, and the artwork, was. The critic Walter Benjamin in 1936wondered why the age of reproduction hadn’t rendered artwork worthless. Penny a copy, everyone could get their paws on a blown-up Michelangelo. Yet prestige, and prices, remained intact. Benjamin’s theory was that the original art remained important because of an elusive quality that was hard to pin down – the aura of the artwork, the presence of pieces in those sacred, hushed, halls of galleries. Benjamin’s writing stemmed in response to a cultural world in upheaval. The academies, the Salons, all those venerated establishments that were the preserve of a cultural elite, had been blown apart. What was to take their place was uncertain. A new speculative market was blossoming, and artists jostled for recognition. In the crowd were new types of visual production, that hesitantly took the name art: lithography and photography.

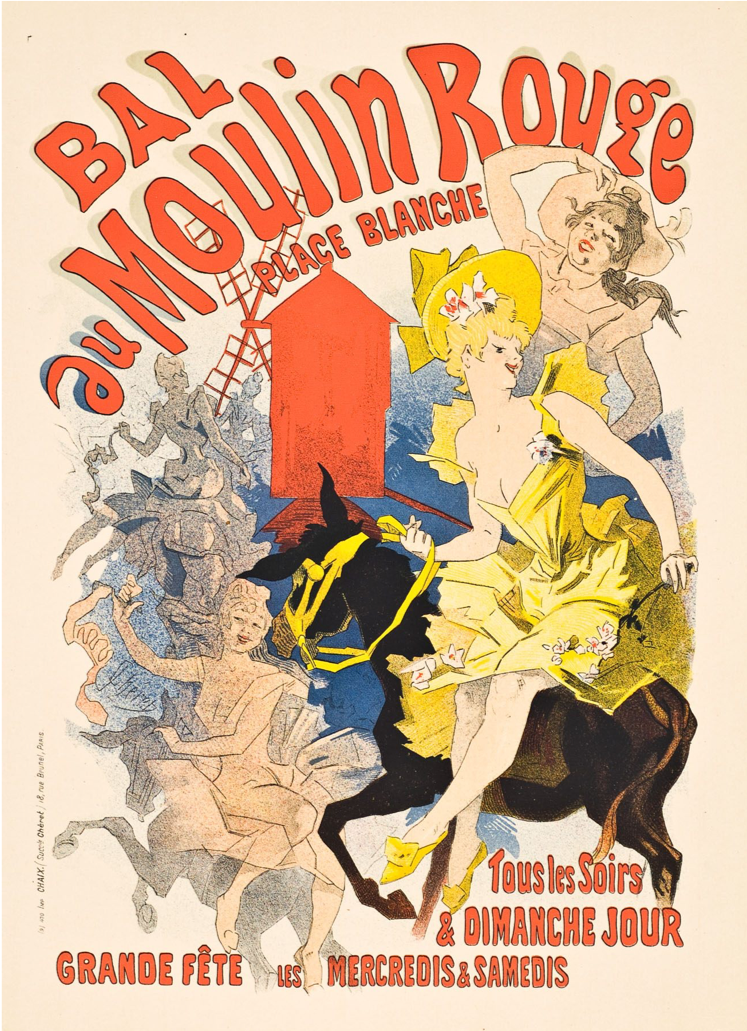

Both had their roots in the nineteenth century. Lithography was in fact invented at the very end of the eighteenth century, but it was really with the figure of Jules Chéret that the art of the poster was born. Smiling dancers caper through his works, embodying the hedonism of fin-de-siècle Paris, with all its garish neuroses and exuberance Designed for new spaces of entertainment – the dance halls, the cafés – avant-garde artists quickly delighted in this proximity to popular culture, and produced bold experiments in the medium. The age of rapidly shifting consumer culture had, it seemed, found its perfect mate in the art of the poster.

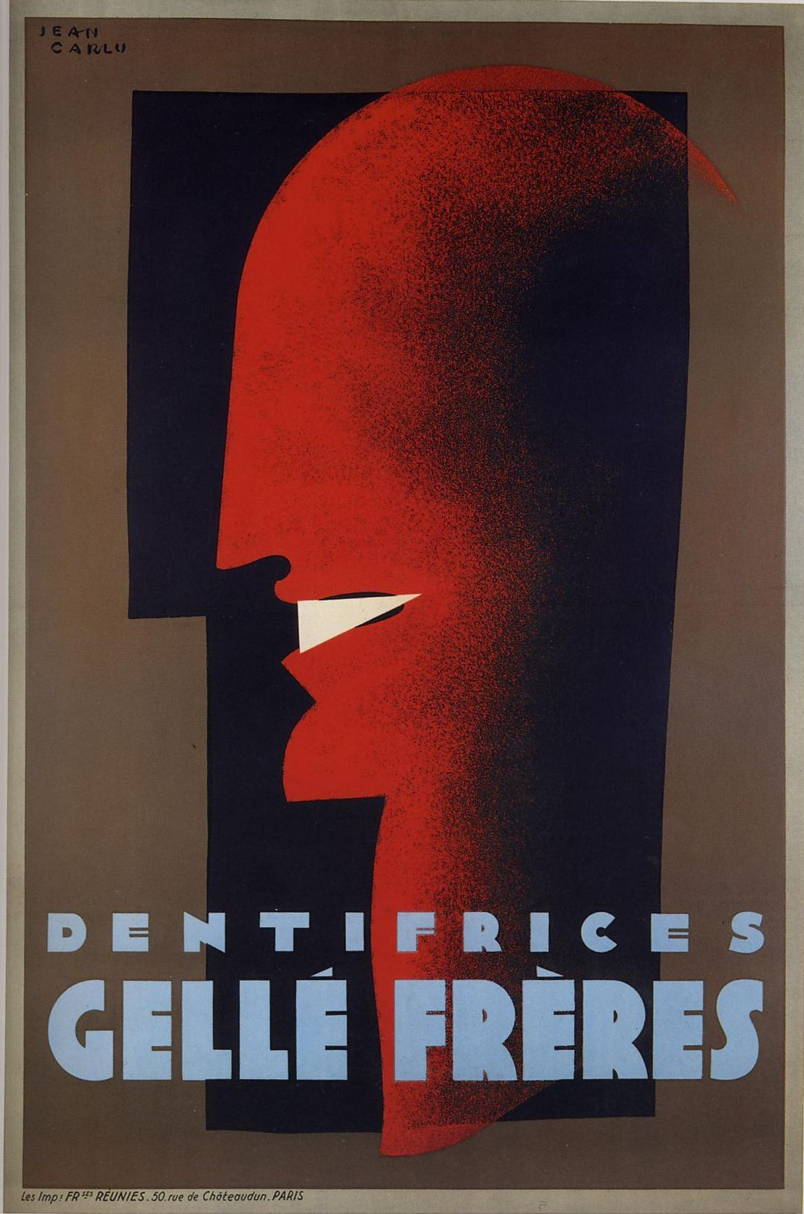

The decadence of the earlier poster was increasingly rejected by artists in Russia and Germany for new principles of functionality, and the call for form to follow function, even to be politically significant. By the 1920s, when our story begins, poster making was an established and viable form of artistic production, even though it had never lost its connection with the commercial world. This double bind, of artistic integrity and consumer necessity, came to the fore with the golden age of poster making in Paris, the age of the four Musketeers: Charles Loupot, A. M. Cassandre, Jean Carlu, and Paul Colin. They were artistic revolutionaries in their own ways. Refining new techniques for producing posters, shaping the style that we now call Art Deco, theirs was a joyous and typically witty vision of the period.

In the words of Apollinaire –

“catalogues, posters, advertisements of all sorts

Believe me, they contain the poetry of our epoch”

– (Taken from the catalogue for The Modern Poster, MoMA, 1988)