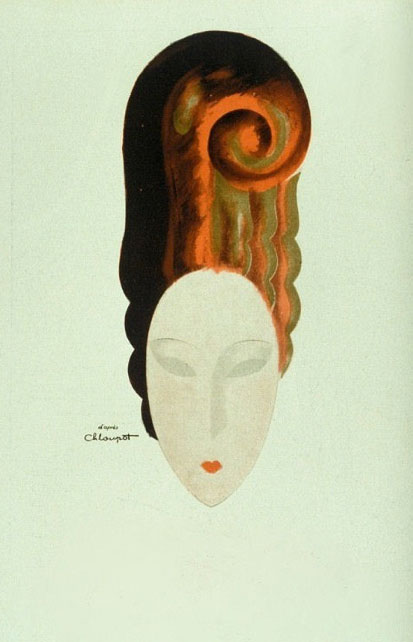

Amongst Charles Loupot’s most striking designs are those that he produced for the leading cosmetic company of the day, L’Oréal. In the Art Deco period, hair styles and cosmetics were changing dramatically, and the public embraced these new opportunities to experiment with their appearances. Leading this social shift was L’Oréal’s founder, Eugène Schueller.

Schueller’s unique combination of both reliable and scientifically tested products, and innovative advertising strategy established L’Oréal as a cosmetic giant, a position that the business continues to hold today.

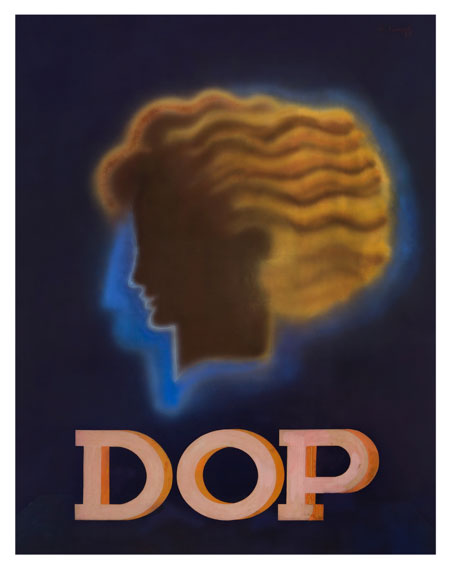

Born in Paris in 1881, Schueller spent his early career lecturing on chemistry at the Sorbonne. His career changed course in 1907, when, working from a two-bedroom apartment, he successfully produced the first stable synthetic hair dye. Schueller sold this product directly to Parisian hairdressers, who favoured the product for its safety and its ability to create subtle colours on their customers. In fact, the hair dye did so well that, in 1909, Schueller founded L’Oréal. A series of ground-breaking commodities followed. 1925 saw the introduction of L’Oréal d’Or, a hair lightener that produced natural golden highlights; in 1929, Schueller invented Imedia, a dye that penetrated the hair fibre itself, and in 1934, the company released the first commercially available soap-free shampoo. Loupot’s design in the following year gives a golden aura to the product, turning hair into a kind of luminous halo.

Despite L’Oréal’s huge success, Schueller’s personal activities in the field of politics were not viewed as favourable. In the 1930s, he was a supporter of the French right-wing organisation ‘La Cagoule’, permitting the group to hold meetings in the L’Oréal headquarters. In 1937, members of ‘La Cagoule’ organised a series of political assassinations. In the 1940s Schueller switched sides, becoming a prominent donor in support of the French Resistance – it is also said that he allowed the Resistance to use a L’Oréal van for a secret mail drop. Yet, this earlier association with ‘La Cagoule’ means that his legacy continues to be highly controversial. While Schueller’s career reshaped both individual appearances and universal beauty standards, his own public image is not as perfectly coiffed as the L’Oréal users we see in Loupot’s posters.