It is often said that Paris was the cultural leader par excellence at the beginning of the twentieth century. From around 1900, until the Second World War, the city hosted a range of major artistic movements that can be loosely grouped together under the umbrella term ‘School of Paris’. Although much critical work since the 1980s has attempted to re-route the course of pure Modernism – the pervasive idea of an avant-garde select living in Paris – there is no doubt that the styles developed in and around Paris left an indelible mark on the visual history of the twentieth century. Two styles, above all, appeared initially dominant: Cubism and Fauvism. Spearheaded by Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse respectively, the two styles – pitted neatly into a war of character between the fiery Picasso and the retiring Matisse – offered two solutions for how to create a language of forms appropriate to the modern age. Cubism broke up forms, distorted them, spun them around, reduced them to puns and shorthands.

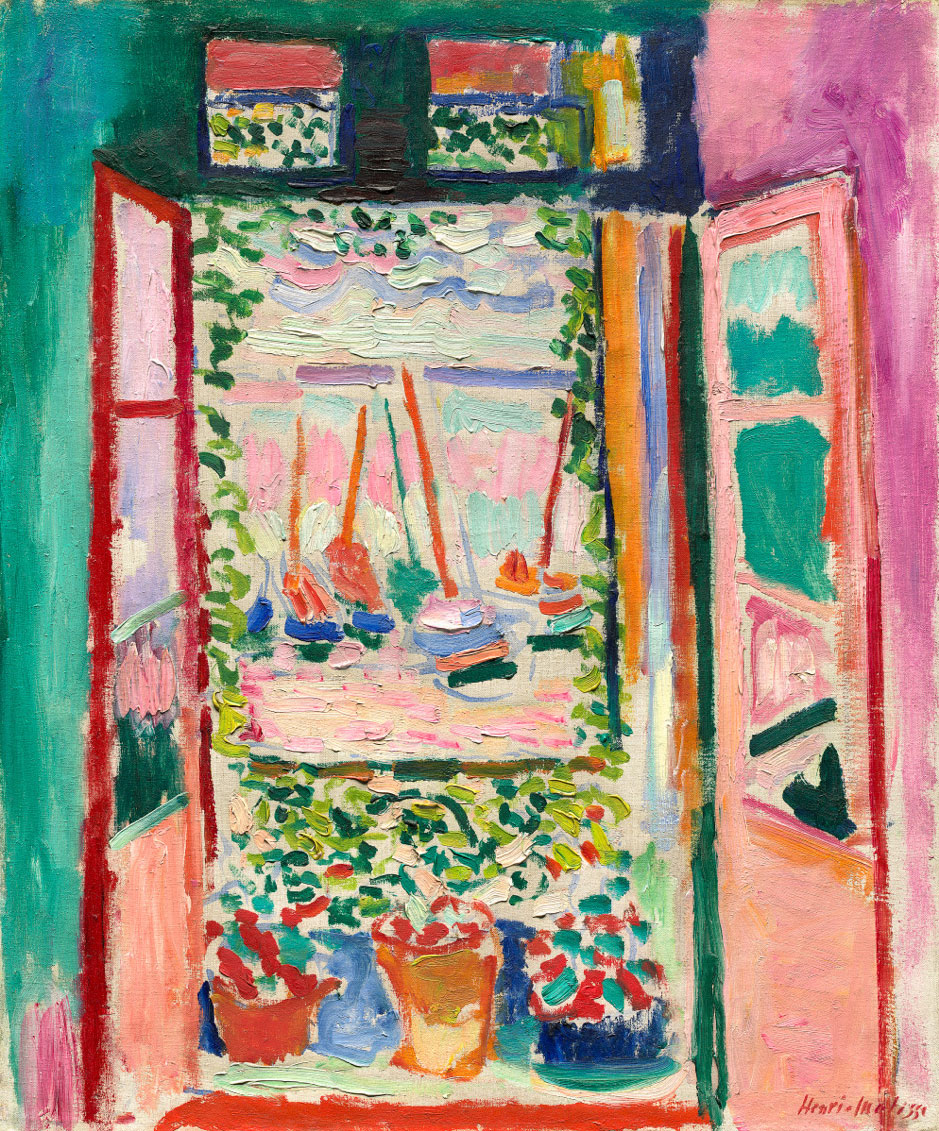

Fauvism blocked in forms of dazzling brightness, with chunky, visible brushwork in which colour spilled out from the structure it was describing.

So persuasive were these styles that it is difficult not to see traces in work that followed. In many cases, this was a conscious strategy, fused with the popular forms of Expressionism and Surrealism. The monochrome stricture of gallery cubism was loosened, an interior dreamworld entered, and following the first world war the human figure was re-introduced (perhaps it had never left).

Artists as diverse as Giorgio de Chirico, Amedo Modigliani and Constantin Brancusi resided in Paris, responded in kind to the rapidly changing world around them. Paris was to keep its supremacy until the Second World War. Artists and writers fled the city, seeking refuge in non-occupied lands. The U.S. beckoned, and Paris fell.

Loupot produced work out of these artistic milieus, drawing from the rich range of possible influences available in Paris, picking especially from cubism and surrealism. It is important, however, that this influence is not cast as a kind of debt, in that the exchange worked both ways. The art of the poster productively informed the work of many artists at the time, vaunted for speed, acuity, and incorporation of the everyday.

Further Reading…

The literature is huge on this topic, but a snappy, and now iconic, introduction is given in Robert Hughes, The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change (1980).